Implied Spaces. A Guide to Armin Mühsam’s Paintings

Catalog or exhibition essays often start out with a description of what there is to see, or they skirt around the semantics of the show’s concept. Others unpack the artist’s key biographical dates. I am not sure what added value such approaches could provide. On the one hand, we can see the work in the exhibition with our own eyes (or reproductions in a catalog); while on the other hand the artist’s biography, read in isolation, does not necessarily hand us the key to his work. To be sure, all his iterations, experiences, joys, and sorrows play a part, but only to the degree that the work of art extracts them from his personal life story and transforms them into intensities many will recognize. Each time this kind of participation happens, it is a leap into the unknown, a potential source of discomfort or anxiety for the viewer. As one communicates with the work of art, the closely guarded conception of one’s self is always confronted with unexpected changes, for leaping can also mean falling. A good catalog or exhibition essay is therefore always a benevolent companion that subtly builds bridges or supplies ladders where one might fall from especially great heights; it leads the way where the work of art recedes into darkness and provides words where there would otherwise be muted silence. Regardless of whether the text is needed or not, at least it doesn’t elevate itself above the art, nor does it claim to do the seeing for the viewer, but rather links the two of them in the process of communication. As you enter into a personal dialog with Armin Mühsam’s work, I would like to offer this essay as such a companion.

Let’s start with first impressions. I look around the show titled “Present Hypotheses.” What do I see? What do I feel?

In order to verbally get a grip on what is visual, I start with keywords: space, space art, art space, architectural forms, objects as such, pared down, flatness, constructed perspectives, stacked and overlapped but not agitated, strange yet satisfying, contemplative. I sense an immensely powerful emptiness.

I am struck by the absence of the person that by all rights should still be present, for who else would have used or wanted to use the stepladder I see in the middle of the room that is pictured in the painting “The Salvaging of an Idea?” Or, to inquire farther into the past, who else would have made the ladder? It becomes evident that humanity isn’t so much absent as merely not pictured, because it has left a trace with all its tools and products. Armin Mühsam’s paintings are devoid of visual protagonists, which are probably even more present for that very reason. This striking presence of absence reminds me of a sentence in Haruki Murakami’s Killing Commendatore: “...that missing element was rapping on the glass window separating presence and absence. I could make out its wordless cry.” Yes, that must be what I initially sensed as powerful emptiness.

Facing the stepladder in the painting is another product: A canvas with geometric forms in front of trees in a landscape. What at first glance seems banal becomes enigmatic upon closer inspection. Are the represented geometric objects themselves artworks that sit in the middle of the painted landscape? – artworks cubed, so to speak? Sculptures within a painting within a painting? If they are sculptures, why don’t they cast shadows like the trees? If, as objects without a shadow, they do not partake in the physics of the painting’s realistically rendered space, in what impossible place are they so precariously stacked? Could it be that what is manifested here is the logic of the canvas itself, the realization that all the three-dimensionality of painting is merely simulated and that every pseudo-spatial unfolding can collapse any time, back into its original state of pure, vibrating color shapes? The other painting depicted in the canvas, whose abstract color stripes faithfully repeat all the hues in the first canvas, might actually enact this very process, as if it was itself absorbing the painted space. Is this what the title speaks of? Is this the idea that is being salvaged?

Once our eye has registered this topological anomaly, it can’t help questioning what initially looked like a clear and intuitive compositional structure. What seemed self-evident to the viewer gradually reveals cracks that become impossible to ignore. Nobody can say whether these cracks won’t become bigger and swallow the whole image, because its depicted space doesn’t seem to have a reliable border separating it from its surrounding space: As soon as you ask about the painting’s frame, the problems multiply – the artist plays a double, even triple trick on us. An art object as a representation within the representation of an exhibition, presented as the view of a space where art is exhibited. It makes one’s head spin, in delight.

Each one of Mühsam’s pieces is rigorously composed. Everything is in its place and deliberately assembled. References to Rene Magritte or Giorgio de Chirico come to mind. What is an image; what is being? What is real? What is perception? Giorgio Morandi once said, “I happen to believe that there is nothing more surreal, nothing more abstract, than reality.” My thoughts continue to spin. What is space? How does one situate? How can I orient myself? Some of Mühsam’s paintings (“Formalist Generalizations”) offer me blueprints. Can they help me find the way? To find my way? Seeking. Getting lost. Finding. Where? In life? Or am I simply there? Nobody asks. It is not possible to draw a really clear line between reality and illusion. The boundary between the two seems to be constantly moving and varying, continuously folding and unfolding in new ways.

Let’s explicitly stick to the exhibition space, because I know a thing or two about it, and we often see it pictured in Armin Mühsam’s paintings. For starters, it is unique in its function as a communal space. You know exactly which rules to follow in a school, a police station, a church, a public restroom. A space where art is shown stands in singular contrast to these locations. We actually enter it expecting an absence of rules, owing to its paradoxical status as a societally sanctioned exception. Its content is undetermined and can therefore be anything: a place for experimenting, a public safe space where questions and relationships are negotiated, a place free of restrictions and thus a refuge, a place for thinking and not a crusty repository of the past. All told, it is a protected space, an island for unrestricted thoughts. Yet: shorelines are in constant flux; islands can be reclaimed by the sea. Societal rules might return to the exhibition space as rigid formalisms. White walls, fluorescent ceiling lights, a particular way to hang the pictures: all this is so familiar to the viewer that he simply doesn’t register it and thus doesn’t realize that the apparent absence of rules has in fact always been part of a normative way of presenting art. By making it an explicit component of his work, Armin Mühsam directs our attention back to this space. The painted exhibition mirrors the real one and brings it into the viewer’s focus as something that all of a sudden cannot be accepted unquestioningly. The abovementioned folding and unfolding of the three-dimensional color space is here joined by the folding and unfolding of the societally coded exhibition space.

What kind of place is this space? What are its characteristics? If we look at it on the most basic level, as white cube, it appears to be the epitome of neutrality. Almost devoid of sensory cues, it demonstrates its exceptional status in our society to the point of negating all traces of humanity, unless the latter is explicitly part of the art work’s content. The exhibition space wants to be the faceless container for the work of art, whose pure presence should be experienced directly, unimpeded, and without distraction.

If Armin Mühsam disagrees with this notion, he does so subtly but deliberately. The white cube is not a vacuum. An exhibition is not merely a presentation of objects but also an accumulation of interspaces, of non-spaces, of voids. The act of showing something always begins with the decision of not showing something else. It is a clear decision to do without. We don’t know whether the stepladder in “The Salvaging of an Idea” is meant to be there for the installation or the de-installation of the exhibition, nor do we know whether the story of the exhibition starts or ends, but the ladder points to something being enacted. It carries into the painting the residue of everything that is tacitly accepted as a precondition for showing a work of art: the curatorial effort of selecting, omitting, and – never without bias – arranging; the physical and often dizzying effort of climbing the ladder and hanging the work. When you enter the actual exhibition space, all traces of this have usually been removed from sight. Mühsam reverses this erasure by mirroring it back into the real space via the painting. The white cube is not a vacuum but the culmination point of cultural practices and decisions, a place where nothing is ever shown neutrally, but where everything is always preferred, channeled, influenced, and canonized. To deny this would be ideology.

The fact that Armin Mühsam’s paintings do not proclaim this insight in a loud and facile manner is a marker of their quality. Instead of agitating, they invite contemplation. Our first glance enjoys the harmony of plane, geometric shape, and color. It would indeed be legitimate to stop at this point. If art is freedom, it is also the freedom to resist the compulsion to engage in theoretical discourse. If we choose to proceed, it turns out, remarkably, that that we do not switch to a metalanguage. We do not add an external discourse; rather, the painting itself guides our eyes to strange details such as the abovementioned absence of cast shadows, which lead to the collapse of the composition’s apparent harmony and coherence. Something is not right. Something is mysterious. A question is born from the painting itself.

We look for reasons in order to understand. We are afraid of the incomprehensible. We associate a Why?, a This is weird! with ignorance, even stupidity. Reasons are constraints in the form of cultural traditions and norms. A teacher asks a question that he could answer himself. I, the student, have to explain or know, otherwise I don’t make the grade and fail. In the context of an exhibition, we are confronted with completely new creations and assignments. It is natural to feel apprehensive about this, but it doesn’t have to be that way. Works of art do not exist so we answer their questions; they exist so we can ask questions with them.

As a curator, I am reminded by Armin Mühsam’s works to continually strive for a language that points things out, one that helps to reveal the ambivalence of the work of art. I find it necessary to speak in a manner where the art is allowed to ask questions rather than provide answers. I want to pay attention to the works of art, to show my respect and care, without locking them into a space already governed by preconceived interpretations, just as one would talk to someone pleasant (if at times difficult) and keep them company on a walk through an unfamiliar landscape. Every dialog is a new conversation, every relationship newly negotiated, every name newly given.

Mirjam C. Wendt, Curator and art historian (2019)

Berlin/Germany

Painting Deconstruction

Armin Mühsam's recent paintings represent an exciting shift in the artist's body of work. Provoked by his desires for personal and aesthetic transformation, these works contain some of the artist's first explorations of line and pattern in painting. They are also complex experiments in deconstruction. In them, he exposes and complicates distinctions between abstraction and representation, creating multiple layers of meaning for viewers to unpack.

Mühsam reached an artistic crossroads in 2015. For almost twenty years prior, the artist painted industrialized landscapes that address humanity's relationship to the environment. Eerily void of figures but replete with human intervention, the artists' clean, precise paintings are both visually pleasing and unsettling. Calm skies and bridled terrain convey a sense of placidity. Manicured plants, precise architectural structures, and construction equipment indicate human efforts to expand their geographical presence and sculpt the natural environment to suit their needs. Clean, smooth surfaces and sharp edges define both natural and industrial elements, creating strange stylized forms that are both recognizable and unfamiliar. The artist's use of earthy colors and three-dimensional space typical of illusionistic landscape paintings draw viewers into a seemingly familiar experience of depicted nature. However, as Mühsam states, "when they actually spend time with it, it's a horror story." The distinctions between natural and human-made forms collapse in his alluring, but entirely artificial landscapes.

Feeling as though his art practice had become as formulaic as his manicured landscapes, the artist set out in search of new ideas to refresh his aesthetic. He put aside his paintbrushes and began collaging colors, patterns, and shapes that he cut from readymade sources such as magazines and books. Mühsam arranged these non-objective cut-outs into layered compositions, filling a small sketchbook with fresh material. The artist also began "collaging in space" at this time. His sculptures, or assemblages, combine wood, acrylic, and other materials that are both manipulated and found. According to the artist, collage functions for him as a "meta-language" that "gives you the zeroes and ones to then recombine in whatever way you want." It helped him expand his visual vocabulary and refresh his compositions. When he began painting again, he did so predominately with the colors and shapes that he discovered while collaging. His explorations in these new mediums gave him the freedom to incorporate elements of geometric abstraction into his precise, three-dimensional compositions for the first time in his artistic career.

Although geometric abstraction is a new addition to Mühsam's iconography, it is not to the artist, who was exposed to western art history during his adolescence in Munich, Germany. His use of abstraction recalls the non-objective works that are often thought to characterize the pinnacle of achievement in twentieth-century modern art. Mühsam depicts straight-edge polygons in flat, unmodulated colors that resemble the formal innovations of the first abstract painters, such as Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich. Unlike these modern artists, however, Mühsam depicts his abstractions within three-dimensional spaces that are based in reality. He foregrounds his geometric shapes against white wall interiors that resemble exhibition spaces and manicured landscapes that call to mind the artist's previous body of work. Placed within the illusionistic space of the canvas, Mühsam's geometric shapes act as both representations of abstract art and nonobjective entities. Their ability to function representationally is underscored when they appear on the walls of exhibition spaces, where they can be interpreted as artworks-within-artworks.

Mühsam also depicts paintings of landscapes in his recent works. Although they retain the denaturalized appearance of his earlier landscapes, the artist no longer pairs them with depictions of industrial architecture. Instead, Mühsam depicts his landscape paintings-within-paintings in exhibition spaces, drawing attention to their artificiality by exposing their metaphorical "frames." Jacques Derrida described the concept of frames, or parergons, as devices that enclose artworks and define their structures and meanings. Although they are created by forces extrinsic to the painting, the conditions under which frames define artworks are often hidden. Uninterrupted, frames inscribe and limit the meanings of art. Derrida argues that frames cannot be recreated or eliminated; they must be disrupted and exposed through the process of deconstruction.

At an educational roundtable in 1994 Derrida stated, "The very meaning and mission of deconstruction is to show that things—texts, institutions, traditions, societies, beliefs, and practices of whatever size and sort you need— do not have definable meanings and determinable missions... and that they exceed the boundaries they currently occupy." Mühsam deconstructs the meanings of abstraction and representation in his recent paintings by depicting both abstract and representational artworks-within-artworks. He complicates the boundaries between the two, exposing their interdependence and shared condition as constructed images.

Elements of geometric abstractions that are distinct from the walls of Mühsam's spaces also resist framing. They can be read as freestanding sculptures or two-dimensional abstractions that are both part of and distinct from the more illusionistic spaces in or on which they appear. Based on colors and shapes that make up his collages, these forms retain aspects of the collage aesthetic. Their sharp edges imply the use of straight-edged tools such as rulers. Their clearly delineated perimeters separate them into self-contained units that appear stacked. By layering forms like collage pieces, Mühsam suggests that they may exist on different planes that recede into space. In many of the paintings, unseen light sources cause geometric forms to cast rigid shadows onto their architectural surroundings, implying that they contain volume. Although layering and shadows situate some of these abstractions within the illusionistic space of the canvas, the frequent absence of surface modeling conveys their flatness and contradicts any implied three-dimensionality. The planar patterning that covers some of their surfaces juxtaposes the spatial depth of the compositions' backgrounds, making viewers aware of the canvas. Bold lines delineate sections of the canvases like drafting notations, drawing viewers' eyes across their surfaces rather than back into illusionistic space.

Mühsam deconstructs the elements of representation that he is familiar with as a trained draftsman and painter. He draws attention to the power of artists to construct realities by creating spaces and forms that oscillate between flatness and three-dimensionality. The nearly ubiquitous presence of the tools of construction in his recent paintings underlines the role of the artist-creator. Ladders, sawhorses, and building materials denote his gallery-like spaces as the built environments of the artist's imagination.

The simplified shapes and exposed structures of Mühsam's geometric abstractions recall the pioneering achievements of Russian Constructivism. In works such as Alexander Rodchenko's Spatial Constructions and El Lissitzky's Proun series, the artists created constructions that lack the hand of the artist and reveal the processes of creation by using raw materials and externalizing the works' structures. Departing from previous artists who developed distinct styles, the Constructivists produced geometric works that could be recreated by non-artists. Their precise, straight-edge forms evoked a machine-made rather than hand-made appearance and blurred the distinctions between art and industrial production. Influenced by the October Revolution of 1917, which brought the Bolsheviks into power and helped to establish the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922, the Constructivists linked art-making to the building of society. They believed that their artworks could work in the service of the Revolution to enact social change.

Mühsam's artworks are not quite as utopian as those of the Constructivists. The geometric abstractions of Mühsam's paintings are often delicately constructed, but impossible. Many are precariously balanced, defying gravity. Some are top heavy and destined to collapse. Others contain illogical structures with conflicting vanishing points and maze-like lines. Their confounding structures are more akin to Op Art of the 1960s, which is characterized by spatial ambiguity and disorienting optical effects. In the artist's own words, these structures are "visualized absurdity."

Mühsam uses the formal language of Constructivism to paint new structures that deconstruct the Constructivist's socio-political artistic mission. Although they aimed to create a new society, the movement ended before the 1930s, never reaching its utopian goals. Speaking about the relationship between his recent paintings and the group, Mühsam stated, "these allusions to Russian Constructivism are also, I suppose, musings on the futility of their kind of utopian thinking that you could change society through art." The artist's nonsensical formal arrangements speak to his perception of Constructivism's unsuccessful efforts to use art for social progress.

Although Mühsam's recent paintings demonstrate the irrationality of utopian pursuits, such as that of the Constructivists, they also reveal an intense respect for and fascination with the possibilities of abstraction. The artist's careful and methodical construction of his impossible forms, evident in the mathematical precision of their conflicting angles and lines, demonstrates the earnestness of his exploration into the Constructivist experiment. Likewise, his complex deconstruction of the meanings of abstraction and representation reveals his analytical interest in the abstract experiments of modern artists. Speaking about his relationship to art history Mühsam stated, "I've always seen myself as simply jumping into the river of art history and letting myself be carried by the water for a while, and then I die and someone else takes my place and does something similar."

Maggie Vaughn, Ph.D. candidate, University of Kansas (2019)

Lawrence, KS

Parallel Sites

Two trains leave the station at the same time in the same direction. We imagine parallel tracks in this case, because how else? Setting aside the improbability that they really leave at the "same" time (as Cratylus, student of Heraclitus, famously posited, one cannot step into the same river once, let alone twice), such wonderfully real-world math problems invite us to understand time and distance in terms of immutable relation. There is something at once romantic and tragic about the parallel as such. Parallel lines do not share a point; parallel planes will not meet. Without the possibility of intersection, the parallel is relation without reconciliation—lines locked in place, untouchable twins. The parallel is entirely dependent upon distance, but nothing in its definition accounts for the scope of that distance. Parallel lines could be a million miles apart. How would they even know that they were parallel, that somewhere out there, they shared something with another?

It is in this interstitial, suspended place that we can first begin to think of the work of Marcie Miller Gross and Armin Mühsam, artist-neighbors with studios separated only by a hallway. (Their studio building, located in the West Bottoms, Kansas City, is unshielded from the sound of passing trains, those low moans and shaky clackings of commerce in motion.) Despite their evident formal differences, Miller Gross and Mühsam share a deep attention to the architecture of expression and to the inescapability of time—historical, art historical, personal, environmental, industrial. They are methodical artists who traffic in otherworldly reflections of the world as it is now, suffused with markers of the past and portents of that which will mark our future.

Their works are equally unpeopled, as it were—free of figuration that would signify flesh in motion—but the profound stillness that they evoke is evidence of the utmost human care. For we, as humans, are on the move, but Miller Gross and Mühsam occupy a parallel in their unequal relationship to this passing of time. Their works speak to the atemporality and outside-time that attends the work of art as such. The duration of the art act. The purposeful, even painful consideration of placement. The alternating currents of deliberation and deferral, of intervention and letting be. Their shared language of architecture and accretion is an ancient one, echoing across eras—forms assembled meticulously, shapes giving way to structures.

It is no surprise, perhaps, that Miller Gross has turned to stacks of wool felt in her recent works. She has long favored the stack as an organizing principle of both her site-specific and her studio work, layering careful pillars of used surgical towels and sweaters—materials that testify to the ephemeral and momentary. A hospital stay, a chill in the air. Felt is one of the earliest known textiles, however, bearing the deep-time traces of experimentation and would-be perfection across millennia. Formed, in many cases, through the compression of tangled fibers, felt is a material that resolves a kind of disorder. As art historian Chris Thompson has written, felt "is a material enactment and embodiment of elements, tendencies, and forces that cohere most effectively because of, and not despite the fact that not all strands have the capacity to connect with any or all others....There is intimate space without each connecting with all, intimacy that exists because of, and not despite, the inability of each genuinely to connect with every other." The composition of felt relies on the intersection and collision of myriad fibers, and yet in this "inability of each genuinely to connect with every other," there is the specter of the parallel line as well, that which is called into being precisely because it disallows connection.

In Miller Gross's work, we are poised between the felt's ancient past and its most modern, industrial incarnation. Miller Gross achieves her strips and segments with a bandsaw, exerting influence over the material that is otherwise willful and intent on its own shape, surprisingly resistant to the rectangular. These cuts rake and pull at the edges of the felt, and upon assembly these built forms often take on an almost singular, blurred surface. But still her creative act retains its primeval imperative, its past-ness. It is gestural, not industrial. We are reminded of the power of combination, even when that combination is not of collage (the assembly of difference), but rather the accumulation of that which is the same. This industrially produced material is transformed through deliberation and choice. The topographic exercise of each layer is especially evident in the works of green and cream felt on plywood shelves. The subtle vagary of Miller Gross's structures at once contrasts and is amplified by the tight packing of the plywood itself—its parallel layers a paean to the precision of machines, to how perfect they can put things together. The relative disarray of the felt stacks is remarkably perceptible in this contrast. In one work, Shelf #2 (moss shear), three embankments of green slabs abut one another, ascending from the plywood base as though bastions protecting something infinitesimally sacred.

The act of looking inflects several of Miller Gross's works in SiteParallels. Deliberate arrangements of felt sculptures on shelves are paired with photographic prints of all-but-amorphous landscapes. These are pictures that the artist took from a train just outside Berlin, and they record a certain impossibility in time. They are oictures of what we don't see, calcified images of moments that should pass and have passed. And yet here we see what was nevertheless there at the right place and time. As Roland Barthes reminds us, just because "the Photograph is ‘modern,' mingled with our noisiest everyday life, does not keep it from having an enigmatic point of inactuality, a strange stasis, the stasis of arrest." Miller Gross's series of felt sculptures followed from these photographs, and one sees in the raked edges of that felt a similar sense of the blurred—discrete elements reaching toward one another, aspiring to connection as time continues to fly by.

There is a sense of the memorial in Miller Gross's work that eschews the grand, desperate-to-play-catch-up statements of American monuments in favor of the subtle ubiquity of those of Europe. Gazing at the ground there, one can learn without breaking stride that this was that, and that that was a long time ago. Miller Gross's largest piece in the show, (2) Slabs, is a floor sculpture comprised of two planes of her compressed wool segments. The scale and placement would suggest the commemorative recognition of an event or a presence, something inscribed in the recordable past. One feels an out-of-focus art historical trace as well: Joseph Beuys, of course, Ann Hamilton, and perhaps even a kinship with Richard Serra's 1969 Skullcracker series from the Kaiser Steel Corporation yard. There is also something tectonic and beyond ancient about this work, however—planes coming together as though plates, colliding. However gentle the curve of the slope and the softness of the surface, there is an implicit violence, a crushing, a rising up.

Lowering yourself as parallel as possible to the floor, you'll notice a small gap created where one plane overcomes the other, a space that accommodates the upward curve of a plane without prescribing a presence to it. This is only one of the points at which Miller Gross's parallel with Armin Mühsam is pronounced, and it is a useful one. Mühsam's most recent works on canvas articulate an array of forms that define space without recourse to the illusion of solidity. Created after a nearly two-year hiatus from canvas, during which he produced a series of sculptures and works on paper using a Czech art book on French Impressionism as a support, these new works depict accumulations of art objects in spaces that recall the rarified stages for the presentation of art: galleries and villas, rooms with windows looking out unto a world of copses of trees. And yet there is an anxiety to these spaces. We are twice-removed from them as viewers of shapes to be viewed. An unseen force (although we know that it's the canvas itself) amplifies our distance from the depicted. One feels the acute ominousness of certain works by de Chirico. Alternately, think David Hockney with a sturdier T-square, or—in Mühsam's deliberate and exacting attention to abstract shape as such—a less ecstatic Tomma Abts.

Much of Mühsam's earlier work had attended to the landscape as an unwitting blank slate for human intervention. In some cases, the results are beautiful, with Mühsam's architectural imagination running free over an otherwise bucolic mise-en-scène. In other cases, the results are predictably late-capitalist: outsized storage units impose boring, boxy volumes on a world with no means of resistance to the grids we've given it. Some of Mühsam's most poignant works of the last few years are those that involve shipping containers—the silent, ubiquitous, and decidedly train-sized cages for commercial products that circumnavigate the globe. One is reminded of freeport art storage hubs, described by Hito Steyerl in Duty Free Art, and the degree to which the containment, transportation, and storage of art has surpassed the presentation of it: "For all we know, the crates could even be empty. It is a museum of the internet era, but a museum of the dark net, where movement is obscured and data-space is clouded." Like Miller Gross, Mühsam is attentive to how technologies of the built environment alter the natural world, and, perhaps more acutely, he invites the question of how human forms coexist within it—from the tables and columns that crop up in works like Strategic Intuitions and Dialectic Classicism to the diagrammatic room designs in Formalist Generalizations that stand in for the networked grids that logic our everyday lives.

Mühsam's newer paintings in SiteParallels offer a world of forms that enclose without displacing, that demarcate self-contained territories while at the same time indulging the flatness afforded by the painting plane. His uncanny interior and exteriors reference a world that exists in an alternate history of art history. This is a world in which one recognizes (at least imagines) certain touchstones, but only through a kind of déjà vu—the hazy, imprecise feeling that you've seen this before, but it's not this. The Salvaging of an Idea depicts the corner of a studio space in which a painting of vertical stripes is hung across from a work depicting a landscape scene that include a canary-yellow polygon (akin, perhaps, to one of Ellsworth Kelly's totems, albeit styled here with far less reserve). The shape is paired on the plane with a pink outline of a parallelogram to its left, delimiting and circumscribing space. As much as the painting (within a painting) seems to depict two works of sculpture, however, their formal presence is that of shapes, not of figures. The trees cast shadows, but the shapes do not. They aren't there, therefore, but they also clearly aren't not. A gray rectangular form in the distance lingers conspicuously beyond the trees. The shape scans as one of the countless, nondescript warehouses or inventory centers that pixelate the American suburban landscape to feed the supply chain of global capitalism.

Georges Didi-Huberman has written that "in each historical object, all times encounter one another, collide, or base themselves plastically on one another, bifurcate, or even become entangled with one another." Time is like the intersecting fibers of Miller Gross's felt—compressed and overlapping at random, reliant on the artist to impose stability. Time is like the shapes and lines that comprise impossible objects on Mühsam's canvases—entangled order, depth without weight. Perhaps the most profound parallel shared by Miller Gross and Mühsam is not a parallel at all, disconnected by definition, but rather that they create work at which intersections convene, becoming even more.

David B. Olsen, Independent writer and editor (2018)

Chicago, IL

Untouched Spaces

Deconstructing the Landscapes of Armin Mühsam

Armin Mühsam paints, what you might name "cultural landscapes", indeed it is the title of one of his early works (Kleine Kulturlandschaft). Quite generally, references to human culture and activity are omnipresent in his work and probably what first strikes the observer. Consequently, his work has been analyzed, not least by himself, in the historical context of, and in opposition to, traditional landscape painting that viewed untouched landscapes as the supreme creation of God. In Mühsam's work His supreme creation is replaced by the, supposedly, inferior works of man. In the words of Leanne Goebel he [Mühsam] is subverting the 19th-century notion of the noble landscape as an expression of God's omnipotence and benevolence and turns it into a sort of "technological sublime" in which the empty and meaningless works of man have replaced those of Creation. In that respect Mühsam himself views his work as the logical conclusion of e.g. Hudson River school painting, which celebrated the untouched American landscape as a manifestation of divine benevolence.

But, last I heard, God is dead and His supreme creation, the untouched landscape, simply doesn't exist and never has existed, like God himself. Consequently, the interpretation of Mühsam's painting as described above becomes difficult to sustain, indeed to understand. Which aspects of landscape are "untouched", "noble", which are "empty and meaningless works"? Is Mühsam's work really so obviously only showing us the destruction of supposedly untouched nature, by our industrial society? And if that is all, is it really worth saying? I can't help seeing more in his work: we learn to apprehend landscapes, the world, in its diversity. And by "apprehend" I mean that Mühsam is providing us with a language that allows us to see the world that surrounds us in a new light. God's creation is replaced by a complex interplay between some unknowable "reality" and the concepts and language we use to represent it. And that language evolves, slowly imperceptibly, but it evolves and therefore also the reality it represents. Mühsam's paintings are actor and witness in that evolution.

Note the presence of the instruments, the trestles, the set squares, the tripods. Those are instruments of construction, construction of the landscapes and the paintings they are represented by. Construction of reality and the language, the signifier, required to manufacture that reality. The construction of landscape, the construction of the meaning of landscape, the meaning of "untouched" landscape. Here the evolution of the painting goes hand in hand with the evolution of the meaning, the signifier evolves with the signified, the painting is our tool to apprehend what "landscape" and "untouched space" is.

Humans are absent. But not only humans, there are also missing spaces, corners and walls that we cannot see behind. In some sense Mühsam is painting the abstract notion of "absence". But not, as the naive interpretation (including the artist himself) would have it the absence of untouched landscape in the 19th century sense, but instead the absence of human traces, and I include all the geometrical elements. Nothing in the paintings represents a human construction with a well-defined and known purpose. Walls seem to be in the middle of nowhere, enclosing nothing. Geometrical shapes are scattered with no obvious use or logic. Tunnels and windows lead nowhere. These are not human landscapes, they are post-human landscapes, quite literally untouched spaces. They seem to abide to their own rules and laws, they have learned to exist of their own right without reference to their creation and creator. These landscapes are not the end of development of a human cycle, they are the end of human development altogether. It is post-human untouched nature. It is what a visitor from outer space might find long after humanity has gone, the post-humanoid natural landscape.

This is visionary art in its purest role. It's a shamanic vision that is helping us to interpret the reality around us and give meaning to it. I see this shamanic role not so much as a warning of a cataclysm [Leanne G.] but as a purely descriptive task redefining meaning and reality of landscape. The painting is here a kind of "pre-dictionary" that lays the ground for the change of meaning and reality of untouched space, and in doing so merely reflects what is already ongoing. What seems so rationally human in the paintings escapes us, there is no logic in its being, no human presence in its function. It becomes part of the land, and vice-versa, the "natural" elements (hills, trees, horizons, clouds, ....) are geometrized and merge with the "un-natural" ones. The distinction between untouched and touched becomes meaningless, and the result is an awe inspiring whole, much like the effect the Yosemite valley might have had on the first humans that set eye on it. And that's where shamanic art comes in, just like Lascaux, it is the way of apprehending, interpreting, and subjugating what we don't understand and do not control. Mühsam, the shaman, teaches us to see what is out there, he lets us name it (at least pictorially) and thus gives us power over it, the power of meaning.

Peter Wolf, Astrophysicist (2013)

Observatoire de Paris, France

Once Internalized, Space Can Be Portrayed

Space may be measured in geographical units but it can also have an emotional dimension. The Swiss travel writer and photographer Ella Maillard wrote during her Afghanistan trip of 1939: "Only those who grasp the expanse of space and allow it to mature can truly claim it." This sentence can be applied almost perfectly to the paintings of Armin Mühsam, even if his work were to address nothing else besides landscape and space. The artist, however, works with much more complex themes. They do not reveal themselves at first glance, and the concept of space eventually achieves a multifaceted and meaningful component. Depth of space turns into deep meaning.

Mühsam paints landscapes that are never unspoiled nature-scapes, but always sophisticated cultivated landscapes. Every one of his paintings portrays human creations of various kinds: architectural, symbolic, cultural, and civilizing. He visualizes these creations through the use of various construction elements, planted vegetation and isolated fragments. The latter function as relics of sorts, sometimes in the shape of railroad and vehicle tracks, at other times in the shape of a historicized industry stuck in an analog mindset, or yet again in the shape of building-block elements abandoned before completion. The sterile cleanliness of his painting style – not a speck of dust has strayed onto his canvas – and the sharp contours, along with the directed light and the resulting shadows suggest a perception that interprets everything as a model of that which is seen. This is also what the ever-recurring painted sawhorses and model boxes are meant to signify. The ghostly vacant and purged locations are reminiscent of Friedrich Nietzsche's descriptions of a nocturnal Turin.

We realize quite quickly: What is being depicted does not represent itself (let alone stand in for just itself), nor does it explain itself sufficiently. Instead, there are symbolic references, dreamlike visions and narrative comments for something that lies outside the image area. The artist is not referring to the topic, but rather to the type; a landscape with buildings is a universally valid concept, with a typical structure and typical features. Mediterranean trees, here and there traces of a shrub, a meadow or a lawn, but never a flower or anything that is in full bloom.

The buildings and structures are clear and simple, with the occasional hint of a quote thrown in: étienne-Louis Boullée's Cenotaphs suggest themselves, while Giorgio Morandi, Giorgio de Chirico and Leo von Klenze serve as influences. The skies and cloud formations reference names such as Philipp Otto Runge and Caspar David Friedrich. All these names are secondary, however, and merely demonstrate that Armin Mühsam knows and has studied his predecessors well.

In addition, there are strange, dark entranceways, concrete-gray underpasses and tunnels, along with bunker- and container-like forms.

Drafting and surveying tools such as straightedges and geographical instruments as well as tripods make it clear to the viewer that planning and construction were necessary to accomplish the motif on the one hand and the painting on the other. This is to say, the artist is referring to the symbolic construction which could once have occurred as part of the narrative depicted in the painting itself, while at the same time referring to his own, complex construction of having composed and painted the image. Communication is symbolized by roads and railroad tracks, transmission towers and satellite dishes.

In fact, Mühsam seems to work like a classic sculptor, and to have removed everything superfluous from the image. The end-product contains only the indispensable – that which has been distilled from a process of observation and subsequent purification. This would also explain the almost viscerally felt emptiness of the image space.

Man is never directly visible, as if the artist wants to tell us: The world now functions without his kind. However, the invisibility of humanity does not automatically imply its absence.

In Mühsam's paintings there are two preferred viewpoints – from above, using an elevated, somewhat remote vantage point, and from eye level.

At the same time, he also offers us his preferred options on how to approach his works: one would be via art and art history, the other via politics and social commentary. In texts about Mühsam the closeness to de Chirico is often written about, mentioning the "Pittura Metafisica," which created a kind of hyperrealism, and to which Mühsam is connected in a distinct, tentative yet noticeable way.

I would like to address another approach, one that prefers to devote itself to the idea of a translation and steers the process of understanding and forming toward the desired result in a free and creative manner. My emphasis here will be on cultural analysis, prompted by clues that are visually apparent as well as implied, without ever having spoken with the artist.

With all of Armin Mühsam's paintings the viewer has the feeling that there is something that cannot be seen. It is as if there was a secret, something mystical, invisible and hidden as we stand guessing in front of the pictures. The questions that arise are: Why is the space devoid of life? What has happened? What kind of nature still exists? Is there any hope of another space, one that has not been emptied out? Which matrix are we dealing with? Where do the dark entrances lead? What is the origin of the strange and peculiarly religious aura in some of the paintings?

While searching for answers, associations and recollections of the films of Russian director and artist Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky become relevant. If the premise is that Mühsam, in mantra-like manner, paints a kind of "zone" comparable to the one in the 1979 film "Stalker," then the art-historical and the socio-political interpretations of his work are able to blend and lead to results that address societal issues in their broadest definition.

An area has been evacuated, closed off, and is guarded by the military. The "stalker," a pathfinder or scout of sorts, makes a living by illegally guiding people past the cordon and taking them inside the zone.

In some ways, Mühsam's mission is the same as the stalker's; we are the ones being led into the zone.

We find examples of this in real life, too: The nuclear disasters of 1986 and 2011, the abandoned tracts of land in Ukraine, around the cities of Chernobyl and Prypiat, and Fukushima in Japan. If we use these catastrophes as starting points, our vague premonitions, which we project into some of the more contemplative paintings, seem to be confirmed: Something is not right here. The time that is depicted in the artworks is as frozen as that in the tale of "Sleeping Beauty." One cannot help but think that there might be no "after," no foreseeable future – not for nature, nor humanity, nor for anything else. Only the recognition of Mühsam's pictorial aims can act like the prince's kiss, lift the curse, and counteract the painter's grave visions.

Art is charged – this applies to Tarkovsky, too – with a noble mission: to actually impart knowledge and comprehension. The apocalyptic mood stands in opposition to the discovery of truth, which allows us to see the "absolute picture" and leads us to the recognition of its shortcomings, which in turn are also our own. Mühsam the artist, just like Tarkovsky the artist, is entirely unselfish; he sees himself and his art as part of a web of reality-based revelations. The only thing that both artists leave up to us is the process of comprehension, along with the route we choose to get there.

It is evident that this is not conveyed through the kind of superficial realism that immediately triggers an eye-opening realization. Mühsam's pictures take us to task. They make demands on our imagination and the grammar of bearing witness, as well as our powers of association and structured thinking. And finally, indeed inevitably, they demand of us to formulate and construct our own understanding. In this intensely absorbing activity our initial intuitions are transformed into the shared knowledge of a poetic, subjective logic. The seemingly peaceful and stable appearance first suggested to us by the artist's iconography, the clear, simplified buildings, the lighting, the isolated fragments and the landscape itself ultimately reveal themselves as an expression of an unstable and invisible system. As viewers, we can engage in this process of recognition via a kind of "mapping". We create our own maps. By blending free association – with all of its unavoidable contradictions – and cognitive techniques of filtering, we engage in a sort of "mind mapping" that ultimately adheres to certain structures of thinking, remembering and experiencing. We can admit that we have not found answers to all the questions and still rest assured that we are being elevated to a new level of understanding. These paintings, though meticulously composed, do not at all spell out fixed meanings.

Within ourselves, the space for contemplation and recognition is expanded, followed by the final conclusion: Those who carry the deep and far-ranging implications of our actions within themselves and allow them to ripen will be able to recognize them.

Claus Friede, Curator (2012)

Kunstforum Markert, Hamburg, Germany

Visual Extirpation in the Paintings of Armin Mühsam

There is a visual mystery to the sparse landscapes painted by Armin Mühsam. The works are austere, yet achingly beautiful, capturing the light and shadows of what might be America or a place entirely fictive. Some paintings feature landscapes with odd industrial objects, structural forms, mechanical or concrete foundations, tanks or overpasses without visible human presence. Others focus on architectural miniatures, a facsimile of a likeness of a built environment. There is a timelessness to the work and an anthropological exploration of signs and symbols, but Mühsam is also deftly reacting and interacting with Western art history. His philosophy and approach are shamanistic in the way Joseph Beuys was considered a shaman, and his technique is similar to the dream writing of Giorgio de Chirico. It's a bit as if Mühsam has yoked the ideas of these two artists (among others) together creating his own philosophy of art making that is metaphysical while visually expressing a contemporary annihilation of sorts.

"My work focuses on the relationship between the natural and the human-built. It is inspired by history, art, architecture and anthropology, as well as my own experience of and relationship to, the environment in all its aspects – geographical, cultural and spatial," Mühsam says.

His landscapes explore places and structures that echo the haunted houses, squares, gardens and railway stations painted by de Chirico. But where de Chirico used the landscape as a backdrop for mysterious symbols and objects, Mühsam finds those symbols and objects in the land with the shadows and perspective just slightly off. Mühsam's paintings of landscape models are the strongest representation of the metaphysical. They have a strange and unfamiliar context. Why a model of the destruction created by mining or the representation of a partially built structure?

Additionally, the exquisite skill in which Mühsam paints is in direct opposition to the subject matter of his work. While not apocalyptic, the perspective is one of destruction. Mühsam is a visual extirpator. And while his sterile paintings are rooted in the traditions of Western landscape painting they have nothing to do with that tradition, which viewed nature as the supreme creation of God and glorified the wonderful land Americans were privileged to inhabit thanks to that God.

"My paintings are the logical conclusion of Hudson River School paintings," Mühsam says, describing George Inness' The Lackawanna Valley from 1856 as "an empty meadow, filled with tree stubs in the middle ground, the railroad and a train passing through. I see in that painting the prophetic beginnings of what I basically am at the tail end of...I'm not comparing myself to Inness, but I think my paintings can be classified as the end point of what is already preconfigured in that painting—A valley just at the beginning of the impact of industrialization."

For Mühsam, the Western capitalistic way of living forged during the time of Inness has led to an absolute equalization and streamlining of the environment. The recurring elements we see in his paintings: underpasses, bridges, utilitarian buildings, shipping containers, tracks on the ground and power lines are a vocabulary, a symbiotic language for logistical efficiency and utilitarianism. This language has complete disregard for place and the individuality of location, and the artist employs it to illustrate the contemporary spirituality that has superseded that of Inness and his fellow landscape painters—a metaphysical and transcendental belief in the idea of progress through the pursuit of material goods. In other words, he is subverting the 19th Century notion of the noble landscape as an expression of God's omnipotence and benevolence and turns it into a sort of "technological sublime" in which the empty and meaningless works of man have replaced those of Creation. Given the economic collapse of 2008 and the financial instability of European markets, belief in economics as our savior requires a supreme and, in Mühsam's view, an also absurd leap of faith.

Another belief expressed in his work is that we humans can continue to manipulate the land and subdue the landscape for our needs. This became evident to Mühsam, who was born in Romania, grew up in Germany and studied art in Montana. When he returned to Germany after earning his MFA, he was struck by how overpopulated, thoroughly cultivated and spatially constricted he found Germany to be.

"After Montana, Germany seemed a horror vision come true – all land is utilized to serve man's purposes. There simply was hardly any place left where our fellow species could live undisturbed; the few who had survived 2000 years of Western civilization were still around by sheer luck and our indulgence," he says.

This is where Joseph Beuys comes into play. Beuys was an early member of the Fluxus movement exploring the fluidity between literature, music and visual art, but it was his political activism (he was one of the founding members of the Green Party in 1979) and his emphasis on overcoming the materialism of Western culture and replacing it with a more holistic view of the world—a gesamtkunstwerk shaping society and politics that most influences Mühsam, dovetailing with his studies of Native American tribal cultures, many of whom also take an interconnected view of society. During his first lecture tour to America, Beuys told audiences that humanity was in an evolving state and that as "spiritual" beings we ought to draw on both our emotions and our thinking as they represent the total energy and creativity for every individual.

Beuys' said: "I don't use shamanism to refer to death, but vice versa – through shamanism, I refer to the fatal character of the times we live in. But at the same time I also point out that the fatal character of the present can be overcome in the future."

"Beuys was not called a "shaman" for nothing." Mühsam says. "To me that is the greatest compliment one can pay the child of a Western civilization. Beuys impressed me with the conviction of his ideas, in the face of overwhelming odds and vicious attacks, especially from fellow artists. He wasn't the only artist of the Twentieth Century who identified the crisis of Western civilization, but nobody else offered a way out of this crisis with such eloquence, seriousness, steadfastness and yes, beauty."

Mühsam continues to point to the obvious destruction of our landscape, our society and our world by our hyper-individual focus and our blind faith in free-for-all enterprise. For Mühsam technology draws into the landscape just as the artist draws on a sheet of paper. Not only are contemporary Western humans disconnected from nature we are disconnected from our own essence. His imagery is like a mirror held up for the viewer in hopes that we will begin to see what we have created and to determine whether we have reached the tipping point for a cataclysm or can yet find redemption. For Mühsam the answer might be that it is too late. What we see in his paintings is all that will be left from our Western profit-oriented economic experiment.

Leanne Goebel, Independent Curator (2012)

Denver, CO

Clear New Worlds

Armin Mühsam engages a semiotic discourse, based on an ambiguity of time as well as of space. He proposes a web of interactions, replacing the duality of man/nature with that of technology/ landscape. His works are comprehensive systems of structures - monuments of concrete, machines and roadways - which are in fact the ruins of a self-destructing society.

There is a big difference between nature as seen through a metaphysical lens and nature as accessible to human perception and reproduced by artists. Thus, Max Friedländer was right to consider landscape as being a reality of a phenomenological order, in the Kantian sense, and not a reality in itself.

One never knows the locations of the places that Armin Mühsam paints but one instantly realizes why humans are absent. Humanity is represented by its destructive fabrications: tunnels, dikes, walls, excavations, roads...an artificial landscape filled with technological architecture, or rather, a landscape as a backdrop for technology.

Mühsam's visualization of this paradox brings into discussion the "beauty" of utilitarianism, but also the wounds it inflicts. Everything that seems to have a logical efficiency, everything that seems to be suited for a new world is actually a sterile world after the disappearance of nature.

Liviana Dan, Curator (2009)

Contemporary Art Gallery of the Brukenthal Museum, Sibiu, Romania

Amerika

Armin Mühsam's starkly beautiful landscapes have garnered acclaim throughout the United States—on the West Coast, in the south, and in the heartland near his adopted hometown of Maryville, Missouri. A number of art critics have praised the mysterious qualities of his work, asking questions such as "Where are these sites?" or perhaps "Why are these landscapes so empty?" Moreover, the artist's skill at creating a sense of timelessness can be seen through characterizations of his paintings as "futuristic;" "records for future use;" and "ambiguous in time and space."

As effective as Mühsam is at creating compelling narratives, the most appealing aspect of his work may be their utter fictiveness. In "Landscape and Tunnel" (2006), one is presented with a painting of an architect's model of a construction project—a facsimile of a facsimile of a built (or about-to-be built) environment. In "Entrance" (2003), we see a tunnel-like structure that seems to have no exit instead of a faithful rendering of an actual tunnel.

So what is "real" in such scenes? Ultimately, the artwork itself becomes the "real" object for apperception. Through such intellectually rewarding ends, Mühsam engages the mainstream art discourses of the past 40 years (in particular, Semiotics). He thus ensures that his work will engender multiple layers of interpretation for many years to come. Timelessness indeed.

James Martin, Curator (2007)

Sprint Nextel Art Collection

Surrealistic Landscapes

Imagine a 21st-century De Chirico set in the flatness of the American plains.

At the Kansas City Artists Coalition, Armin Mühsam's visions of abandoned technological detritus in outdoor settings have exactly this feel.

It's an ambitious show from the Romanian-born artist, an assistant professor of art at Northwest Missouri State University in Maryville. The exhibition comprises more than 30 paintings, watercolors and drawings.

The sheer volume of work imparts urgency to Mühsam's theme of our powerful but self-destructive relationship to the environment.

Among the most compelling pieces are a series of charcoal and acrylic drawings that could have been ripped from the pad of a futuristic civil engineer. But Mühsam's handling endows these lifeless scenes of dikes, tunnels, power lines, trenches and tanks with a formal grace and expressiveness that transcend deadpan architectural draftsmanship.

Shading, hatching and washy passages index the artist's hand and hint at an underlying emotional relationship with his topic.

An intriguing group of acrylic paintings titled, simply, "Compositions," presents boxy prefab construction components, including a highway overpass, like minimalist sculptures in the landscape. Overbearing, mannered, even distracting, the gestural paint handling Mühsam brings to their desolate surroundings exists in tension with the simple geometric forms of his manmade subjects.

Yet it feels right - with "wild" paint acting as agent of wild nature, vowing to reassert itself over the encroachments of cement and steel.

Mühsam's visions offer a painful, 21st-century contrast with the 20th-century Precisionists' view of the industrial landscape as a source of promise, productivity and pride. And their astringency sets them apart from the imaginary landscapes of other contemporary artists, seen in profusion in the Kemper Museum's current "Phantasmania" show.

Alice Thorson

Kansas City Star, June 2007

Vistas of a Post-Natural World

There's a certain quality inherent in a landscape painting that is rarely pointed out in art: the eternal. Trees, rolling hills, a cloud-filled sky – these natural elements go on through time and are basically the same today as they were in the 16th century and as they will be in the 23rd century.

Though it wouldn't appear so at first glance, this eternal quality is a key element in the landscapes by Romania-born artist Armin Mühsam.

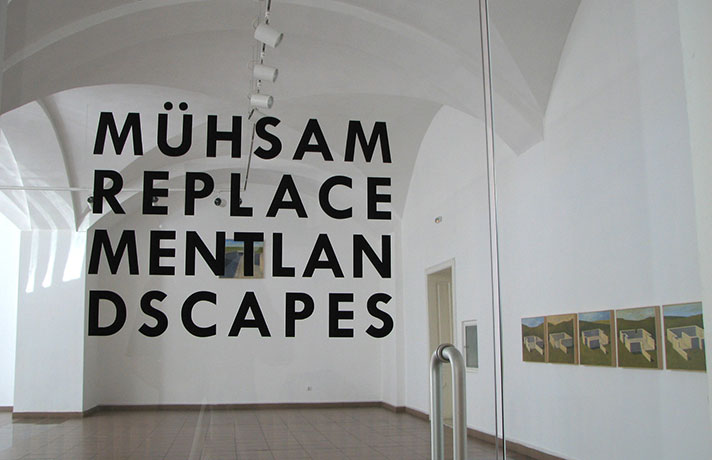

Mühsam's oil paint vistas, on view in Replacement Landscapes at MetroLex Gallery in downtown Lexington, offer the viewer a twist on the eternal. His landscapes focus on those that modern man has created: a panorama populated by structures, manufactured by technology and beautiful to the ordered eye.

"Technology (read: Western Man) writes or draws into a landscape just like an artist would draw on a sheet of paper," Mühsam writes in his artist statement.

"Because technology envelops us so thoroughly we accept it as the only possible reality. The more we are enclosed by it, the less we notice that we lose touch with the natural, unmediated world. (The paintings) are man-made replacement landscapes – sterile worlds after the disappearance of the natural."

An example of Mühsam's notion of the replacement of the real is Model of an Industrial Landscape. Here a tabletop model of a group of familiarly flat-colored geometric shapes spew white smoke or steam against a window view of red rooftops hidden among trees and sky.

The model, seated within a blank interior space, is a generic layout of an industrial complex, but the balance of shape and color draws the eye across the painting in an aesthetic appreciation of modern form – an appreciation that does not fully extend to the "real" view of houses beyond.

Though the works are meant as records for future use – landscapes for a world where the outside is lost – they also contain echoes of the past. That is where their strength truly lies.

The painted train tracks in many of the works recall Roman aqueducts, the Great Wall of China and the Nazca Lines of Peru – ancient technology still present in contemporary landscape.

Mühsam's presentation of today's structures, the manner of their use and how they affect our lives provide not merely a vista that replaces what's destroyed but also an eternal mark of our presence and value system.

Strategic Location is more typical of the show in its standard outdoor landscape format. Here, a deserted broadcast tower reaches from its low building to the cloud-filled Midwestern sky.

Undeniably technologically oriented, the tower functions as the visual connector between the earth and sky, intertwining then as nothing else in the picture plane can attempt. It also functions as an expression of humanity's attempted interconnection and dominance of all natural phenomena.

Ultimately, Mühsam's simulacra paintings function as traditional landscape paintings: They are idealized, unpopulated and conceptual vistas of the outside world. In other words, these landscapes, fake views of tomorrow's world, are just as fake as Monet's water lilies of yesteryear.

Rather than presenting pretty images to distract viewers from a turbulent world, Mühsam's vistas present us with a conception of the modern landscape seen outside our time: preserved, maintained, no longer functional but purely aesthetic.

Their significance then lies in their contemporary understanding of that aesthetic, which in Mühsam's case is the shape and focus of the modern environmental experience.

Heather Castro

Lexington Herald-Leader, May 2007

Land Scapes

Armin Mühsam's exhibition, Constructed Landscapes, might just as easily be titled Variations on a Theme, an aesthetic concept that undeniably applies to his process. Mühsam's paintings all show architectural forms in various stages of construction. In the statement accompanying the show, Mühsam describes how the virtual space of his landscape paintings correlates to the actual space of real buildings in the man-made landscape. Mühsam envisions the construction site as an artistic playground where shapes and forms are subject to the manipulative powers of the artist It's a grown-up's version of playing with blocks.

Because ambiguity of time and space plays a key role in Mühsam's paintings, entropy and potential face off in a curious tension. For example, Mühsam's "Sketch of a Landscape" (2003) contrasts a half-finished (or half-erased?) rectangular structure sitting alone in a field with a finished landscape incorporating the same structure. In viewing this diptych, one senses potential in the structure's creation while at the same time realizing its futility. Because neither version appears to be in use, the structure could as easily be in the process of disappearing as in the process of appearing.

Mühsam's variations are most literal in his "Foundation Series" (2002), which includes five paintings that depict the erected ground walls of a single building nestled in a shallow valley. As the artist tries one configuration of the walls, then another, the pictures bring to mind those mathematical equations that can generate an infinite number of patterns. Time stands still in this series of paintings, as shadows marking the sun's angle remain consistent. Yet the series retains a feeling of progression. The technology that was used to build these structures has been twice removed: first by the absence from the pictures of the building mechanisms (e.g. cranes, bulldozers, etc.), and then again by the artists playful reimaginations of the site.

As conventionally beautiful romantic landscapes, these artificial constructions fall short. Mühsam's work is too stark and straightforward to initiate thoughts of Platonic Beauty and Truth. Instead, we see them for what they are: exercises in architectural shape-shifting where form decidedly trumps function.

Heather Jeno

Santa Barbara Independent, February 2005

Surreal Estates

Looking at the strangely lean spaces and clean, angular views in the paintings of Armin Mühsam, now at the Atkinson Gallery at Santa Barbara City College, one name leaps to mind: Giorgio de Chirico. Like protosurrealist de Chirico, Mühsam relishes the interaction of peculiar structures and shadows, and of geometries laid out on enigmatic grids and odd landscapes.

Also like de Chirico, Mühsam - who studied in Germany and the United States and is now based in Missouri - creates art relating to the realm of dreams as much as to concrete reality.

The artist piques our interest even as he artfully frustrates our understanding of what we're actually looking at. He relies on a visual vocabulary of building-block forms, mazes, foundations for unexplained buildings and other ersatz works-in-progress.

The show's title, "Constructed Landscapes," relates most directly to the painting in the "Landscape Model" series. In this piece, a miniature landscape tableau, like something from an elaborate model train layout, is propped up on sawhorses and adorned with primary colored streamers. A wash of sky and clouds is painted on the wall behind it, toying with our sense of reality and contextual reference, in a Magritte-like way.

These paintings may appear to be blueprints or work studies, but, in fact, serve as destinations and declarations. But we're happily duped, lured into the artist's clean and confident aesthetic flair.

"Project for a River," for instance, consists of diptychs with one panel deliberately left unfinished, and celebrating that very lack of finish. The six paintings in the "Foundation" series depict mysterious naked walls in a generic green hillside setting. The floor design differs slightly in each piece, like variations on a musical theme with no clear beginning or ending.

We seem to find more of a definable "there there" (to quote Gertrude Stein's comment about Oakland) in "After Klenze," referring to 19th-century neo-classical German architect Leo von Klenze. And yet its skeletal structure built into a hillside is similarly elusive. Puffy clouds hover overhead and a dirt road wends its way toward the polymorphic structure, but no clear motive announces itself. Muhsatn appears to recognize that architecture without motive can be scary.

However much he inserts irrational angles into his painting, Mühsam also maintains a sense of order on his own terms. The painting called "Signorelli's Tree" is another scenario set up on hobby horses, as if to suggest the touch of the enlightened hobbyist. Long de Chirico shadows creep around the picture and a lean tree lurks with a quiet grace in the distance.

All the pieces and geometric elements are organized with a neatness and calculation extending beyond the, generally messy world we inhabit. That's where the artist's artistic otherworldliness fits in, convincing us that the not-quite-real "constructed landscapes" contain their own truths.

Josef Woodland

Santa Barbara News-Press, February 2005

Surreal Emptiness

On view in the back gallery at Leedy-Voulkos are the smart, challenging recent paintings of German-born artist Armin Mühsam, which provide a more conceptual and decidedly post-modern counterpoint to Butt's expressions. Although reared in Munich, Mühsam earned a master of fine arts in painting from Montana State University in Bozeman in 1997 and is currently assistant professor of art at Northwest Missouri State University.

While perhaps best described as landscapes, Mühsam's paintings depict an eerie, imagined world marked by the impact of modern technologies. Uninhabited, their surreal emptiness and deliberate artificiality (often furthered by keyed up color) recall the work of Giorgio de Chirico. Yet, while Mühsam speaks to a tendency to exchange one set of "machines" for the next in the name of efficiency (which might characterize the entire 20th century), his well-crafted paintings evidence distinctly contemporary iconography. Alongside abandoned bridges and excavation holes, satellite dishes emit signals to far-off receptors.

Throughout Mühsam's work runs a sense of abandonment of the once cherished and new. Bridges or dikes leading off to distant horizons end abruptly in the foreground, telephone lines criss-cross to form abstract patterns across the sky, seemingly disconnected from any function. These traces of man's intervention are set into sweeping vistas, juxtaposed against verdant rolling hills and clusters of deep green trees and bushes, so as to amplify their constructed nature as well as to highlight the notion that we are constantly manipulating the landscape to suit our wants and needs.

What makes these works so engaging, ultimately, is the undeniable beauty Mühsam achieves in spite of the disconcerting strangeness of the sites he depicts. As the artist states, "when I paint an artificial landscape in the most beautiful manner possible I challenge people to reconsider their expectations of beauty."

Kate Hackman

Kansas City Star, May 2001